A First Taste of Game Jams

In late 2024, I became interested in participating in my first game jam. My primary goal was to gain well-rounded experience and challenge myself. I had never fully developed a game to completion, and I felt it would be immensely valuable to do so.

I teamed up with my previous coworkers Bryan (3D Artist) and Rian (Designer). Bryan was in charge of pretty much all the models and VFX, Rian handled much of the game design, level design, and balancing, and I was the sole programmer. In addition, I produced the music and SFX for the game. Special thanks to Ashna who helped out in various bits of development and modeling.

After a month of hard work and late nights, this is our entry: Orbital Decay. (Please don’t hesitate to check it out! A full playthrough takes less than ten minutes.)

A simple trailer for our game:

What I’ve Learned

Before getting into any details about the jam, I will outline what I’ve accomplished and learned in this project:

- Developing a game to completion

This is what I set out to do, and it was successful. I was involved in every step of the process, from brainstorming concepts and creating a GDD, to coding, writing dialogue, designing SFX, composing music, running playtests, debugging, dissecting feedback, creating a trailer, designing a webpage, shipping the game, and so on. The experience gained from this was immense.

- Leading a project

As the sole programmer, I played a central role in nearly every decision and detail of the game. This was an excellent learning experience. Godot, by nature, is more programmer-centric—for example, it lacks an equivalent to UE5 Blueprints. This meant I had to solve most technical issues and make crucial decisions regarding scope and implementation to ensure a successful end product. There was no senior developer to turn to… I was the most senior programmer in our group! It is very rewarding to be able to say that I solved every problem I encountered myself.

- Broadening my skill set

Being involved in the full development cycle allowed me to explore aspects of game development that wouldn’t be possible in a larger team or project. This was my first time implementing enemies from start to finish. Bryan provided models and animations, and I used Godot’s AnimationTree and StateMachines (controlled via code) to implement all enemy behaviors.

This was also the first time I worked on SFX (and music specifically for video games). It was a fun and insightful challenge to work within our thematic constraints. In addition, I had to really churn out every single track and piece of audio within a couple days of time, and I am quite happy with the results. You can check out the soundtrack here.

- Understanding and working with feedback

I prioritized gathering player feedback. I regularly sent builds to friends and recorded their thoughts on various aspects of the game. Near completion, I shared builds with people unfamiliar with the game and watched them stream their playthroughs without offering guidance. This was crucial for balancing, understanding player behavior, and improving clarity (such as refining the tutorial sequence). By iterating through build and feedback cycles, we significantly enhanced the player experience and eliminated potential pain points.

- Pushing the envelope

One of my favorite features in the game is the diegetic user interface. The dialogue and power-up selection panels exist in 3D space, tracking the cursor and tilting toward it. I had a lot of fun figuring out the math behind this, and the result feels polished and immersive.

- Working under time pressure

Originally, we had two programmers. However, about a week into development, our other programmer had to leave the project due to extenuating circumstances. This was a tricky crisis; our original scope assumed that we had two people who could work on code, and suddenly we had bitten off more than we could chew. Despite this, I was able to rescope where possible and tightly adhere to a schedule with set milestones. By putting in lots of overtime and staying extremely disciplined in development strategy, we were able to produce a game without significant compromise that fulfilled our original vision, despite the difficult position.

The Game

The game itself is a 3D top-down bullet-heaven, with sci-fi and horror themes. We chose the bullet heaven genre as an interesting challenge: we also believed that it would be an uncommon choice of genre in the jam. As it turns out, we were right; even after checking out over a combined 200 other entries, we didn’t find any other games like ours!

This year’s theme was “Spin”, which was implemented in our game as a hybrid melee-attack and reload: the player must spin their mouse around the player’s robot to reload, which also launches a melee attack that pushes enemies away.

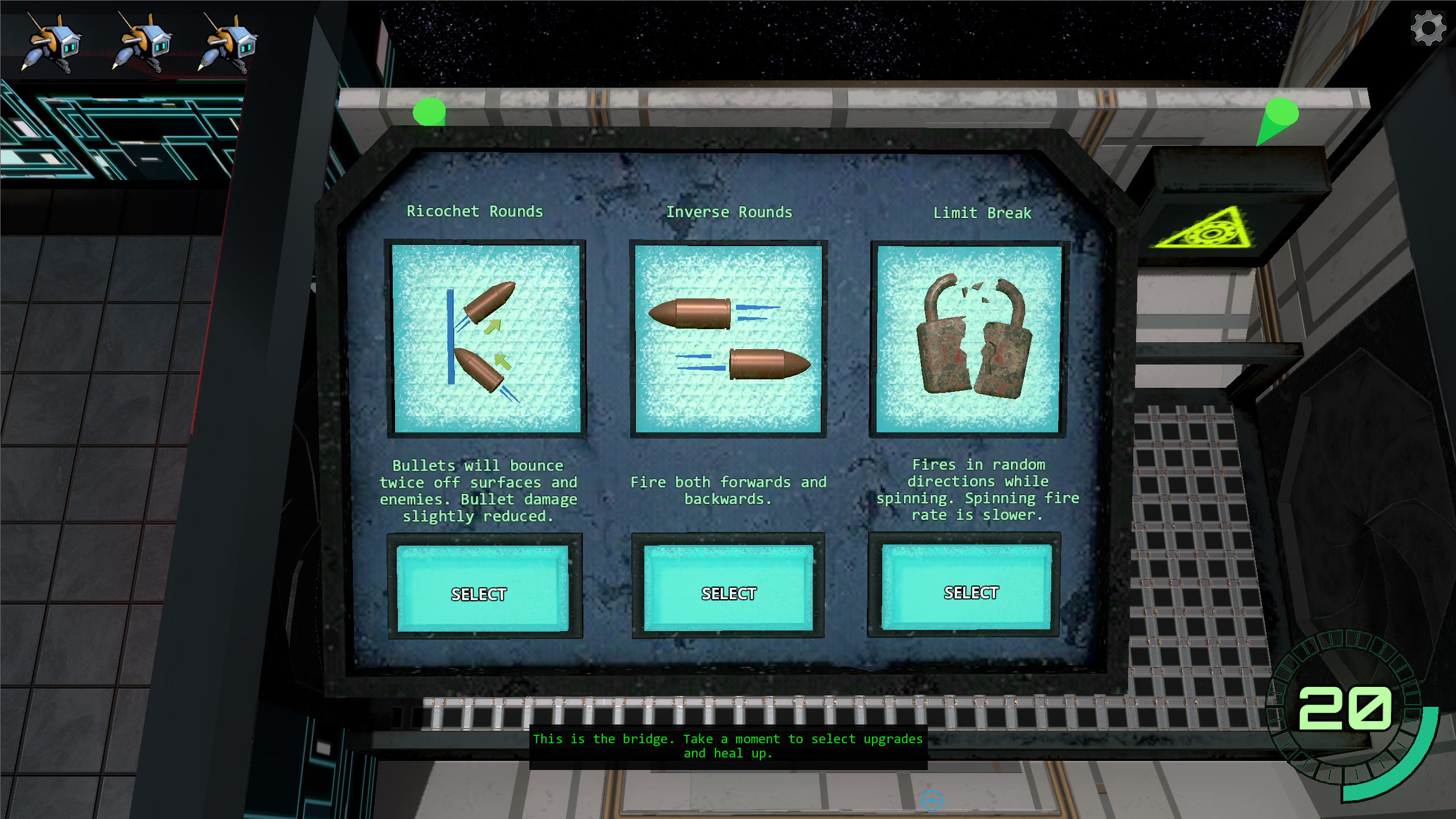

As you progress through the bosses, you are routinely given a choice of different powerups, ranging from basic stat boosts to entire new abilities. Much like other staples in the bullet-heaven genre, these abilities require absolutely no extra controls, and are either completely automatic or are activated upon simple conditions such as running out of ammo. This was the most important pillar of our game that created variety, provided interesting decisions for the player, and allowed fun synergies and combinations that gave a sense of power and progression. Consequentially, each playthrough of the game is unique. I am super happy to say that this idea turned out to be a great success and received the most positive feedback from players.

The Godot Game Engine

A choice we made early on was to try using Godot. None of us had prior experience with the engine, and we all wanted to see what it was like. In addition, our usual choice of Unreal Engine 5 does not export to the web, and we were hoping that it would be possible to keep our game as a web submission. Unfortunately, our time constraints prevented sufficient optimizations for a web build, and our game suffered from lag spikes due to browser limitations, and in the end we opted to stay with an executable instead.

It is clear why Godot is so widely used for game jams: it is incredibly lightweight and has a simple node-based design philosophy, allowing extremely quick prototyping. This is also aided by GDScript, Godot’s tightly-integrated scripting language, which allows quick and simple logic via easy-to-attach scripts.

Having finished a game with Godot, I am happy to say that I’ve added the engine to my repertoire and can work comfortably in it. With further updates to engine features, I wouldn’t be surprised if more game studios started using Godot in the future.

However, GDScript suffers from many missing features that are taken from granted in more mature and low-level languages like C++. One of the absolute biggest pain points was the lackluster debugger, which often provided limited information and slowed down bug-fixing. This was thankfully mitigated by the fact that I was the sole programmer, making it much easier for me to figure out why something wasn’t working (because I wrote all of it). Certain language features like interfaces didn’t exist, and it wasn’t easy to enforce many coding practices beyond basic procedures such as strongly-typed variables. Another thing I didn’t really enjoy was the heavy usage of string literals: for example, to play a specific animation, you had to directly reference its name and library in a string in the code, which is very rigid. While this was mostly just an annoyance for our jam, it is easy to see how this can quickly become untenable as a project scales further.

Conclusion

Our game placed 92nd out of nearly a thousand entries—an achievement I consider a monumental success. Not only did we complete our first full game, we also did it in a completely foreign engine, with less firepower than we expected. A top 100 finish is, in my opinion, something to be celebrated. I’ve learned an immense amount and gained invaluable experience. I will continue working with Bryan and Rian on new projects and continue to advance my skills as a developer and creator. Thanks for reading!