Chapter 5 of 3D Game Programming with DirectX 12 has an introduction to the Rendering Pipeline, and brief description of each step. This chapter is heavier on theory, and chapter 6 delves into the code.

Computer Color

Before we get into the pipeline itself, it is worth it to first go over color representation. Depending on the use case, there are multiple ways that colors are represented in code. For example, to describe the intensities of light, we use a normalized range from 0 to 1 for RGB. We can also apply vector operations to color vectors, such as adding colors to each other or subtracting them from each other. We can also do scalar multiplication to manipulate the intensity of the light. Since we may need to modify the intensity of individual channels, we define componentwise multiplication as follows:

(x, y, z) ⊗ (r, g, b) = (xr, yg, zb).

This is useful, for example, in raytracing: a surface may absorb a portion of red, green, and blue light from a ray. Note that for all the operations described, we need to clamp the result from 0.0 to 1.0.

For 128-Bit Color, we have an additional color component called alpha, commonly used for the opacity of our color. 1.0 is fully opaque, and 0.0 is fully transparent. Since this is just a 4D vector, we can use the XMVector type and take advantage of SIMD for calculations.

For 32-Bit Color, we have 8 bits for each component, giving a total of 256 shades of each. Typically 128-bit color is used when we need more precision so that less error accumulates. For the back buffer, 32-bit color suffices, since apparently display devices currently aren’t able to take advantage of higher resolution color.

The Rendering Pipeline

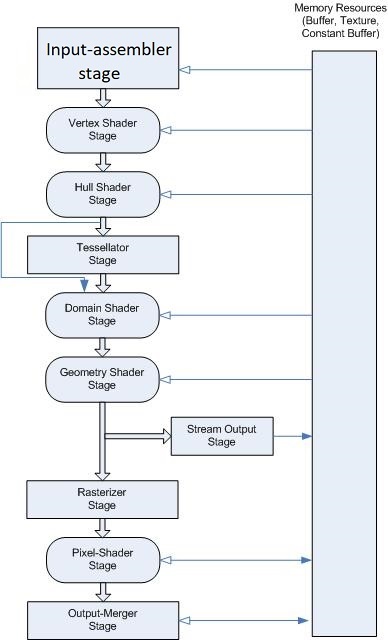

Microsoft has this page on the graphics pipeline that matches the book’s overview, and has this graphic:

Interestingly, if you search for “Rendering Pipeline” online, the steps seem to vary a lot between different graphics APIs and sources.

The Input Assembler Stage

The input assembler (IA) reads geometric data from memory and assembles primitives. Basically, it reads vertices and indices data to make triangles (and lines and points). In DirectX, vertices are actually more general than just primitive points - they can contain additional data, such as normal vectors and texture coordinates. We are allowed to define the vertex format as required for whatever use case.

Vertices are bound to the pipeline via vertex buffers, which are just lists of vertices in contiguous memory. The way the vertices are interpreted is defined by a specified primitive topology. Some (not exhaustive) examples:

- Point list. Each vertex is an individual point.

- Line strip. All the vertices form a line.

- Line List. Each two vertices define individual lines.

- Triangle strip. Three vertices form each triangle, however, the last two vertices of each triangle is shared with the next triangle. There are n-2 triangles for n vertices. Note that the GPU swaps the winding order for even triangles to avoid unintended backface culling (more on that later).

- Triangle List. Every three vertices form an individual triangle. 3n vertices form n triangles.

- Primitives with Adjacency. A triangle list with adjacency includes a triangle’s three neighboring triangles (called adjacent triangles). 6n vertices form n triangles.

Oftentimes vertices are duplicated, perhaps even a lot, since we cannot always use triangle strips to define every shape. In the interest of efficiency, we specify an index list and only unique vertices in our vertex list. The index list will specify the correct indices in the vertex list to build our triangles. Integers take up less memory, and with good vertex cache ordering, the GPU won’t need to do duplicates as often.

The Vertex Shader Stage

The vertices are then fed into a vertex shader, which can just be thought of as calling a function on every vertex:

for (UINT i = 0; i < numVertices; ++i)

{

outputVertex[i] = VertexShader(inputVertex[i]);

}

The vertex shader can do things like transformations, lighting, and displacement mapping. It is something we implement.

// Local Space and World Space

Instead of directly working with world space coordinates, it makes sense to build objects with a local coordinate system, and then later place it in the global scene by executing a change of coordinates transformation. This process is called a world transform (the corresponding matrix is the world matrix). Many advantages come immediately from setting things up this way:

- It is much easier to define objects with a convenient local coordinate system, such as a cube, which can be fully described with just two vertices.

- The object can be used across multiple scenes.

- The object may be used multiplee times in a single scene.

Our world matrix W can be approached easily and intuitively as a sequence of transformations W = SRT, where S is a scaling matrix, R is a rotation matrix, and T is a translation matrix. Another way to approach the world transform is to take the local space coordinates and treat them as world space coordinates, and then apply a sequence of transformations on your object(s) to the desired scale(s), rotation(s) and position(s).

// View Space

The camera itself also has a coordinate system, called view space, eye space, or camera space. In the book, the convention is that the camera looks down the +z-axis, the +x-axis aims to the right of the camera, and the +y-axis aims above.

The volume of space that the camera sees is described by a frustum, defined by a near plane n, a far plane f, vertical FOV angle α and aspect ratio r. Since the near/far plane are parallel to the xy-plane, they are simply defined by their distance from the eye point. The horizontal FOV angle β can be calculated.

In the frustum, a vertex v has a line of projection to the eye point. A perspective projection transformation transforms a 3D vertex v to a point v’, the point where the line of projection of v intersects the 2D projection plane. Note that the projection plane is not the near plane. Since the actual dimensions of the projection plane don’t matter, we set the height h to a convenient value of h = 2.

The coordinates of points on the projection plane are in view space, which causes a problem - the dimensions depend on our aspect ratio r. To remove this dependency on the aspect ratio, we normalize the x-coordinate from [-r, r] to [-1, 1]:

-r ≤ x' ≤ r

-1 ≤ x' / r ≤ 1

After this mapping, coordinates are said to be normalized device coordinates (NDC), and a point (x,y,z) is inside the frustum if and only if:

-1 ≤ x' / r ≤ 1

-1 ≤ y' ≤ 1

n ≤ z ≤ f

Recall that n, f are the distances of the near and far planes. Our NDC coordinates have a height and width of 2, so the fixed dimensions mean our hardware doesn’t need to care about aspect ratio, and the hardware assumes that we will always supply NDC coordinates.

The Tesselation Stage

Tesselation is when we subdivide the triangles of a mesh to create finer detail. This is how level-of-detail (LOD) works, where triangles that are far from the camera are not tesselated, so we can focus detail where it can actually be appreciated by the viewer. Also, animation and physics are done on simpler low-poly meshes for the sake of performance. This stage is optional.

The Geometry Shader Stage

This stage is also optional. The geometry shader inputs entire primitives. The main advantage is that it can create or destroy geometry, such as expanding a primitive into one or more other primitives, or not output a primitive based on some condition. The book is very brief here, and more in-depth discussion will happen later.

Clipping

Geometry completely outside of the frustum needs to be discarded, and intersecting geometry must be clipped, leaving only what is inside the frustum. Thankfully, we do not need to care how this is done, because it is done for us by the hardware.

The Rasterization Stage

This stage is where we compute the pixel colors from the projected 3D triangles. After clipping, this is where we do the perspective divide to transform from homogenous space to NDC. After, the 2D x and y coordinates are transformed to a rectangle on the back buffer called the viewport. After this, the coordinates are in units of pixels.

// Backface Culling

To distinguish which direction a triangle is facing, we follow a convention. Given vertices v0, v1, v2, we compute the following:

e0 = v1 - v0

e1 = v2 - v0

n = (e0 × e1) / ||e0 × e1||

The side which the normal points out of is the front side. A triangle is front-facing if the viewer sees the front side, and back-facing if otherwise. What’s important to see is that a front-facing triangle’s vertices are ordered clockwise, and a back-facing triangle is ordered counterclockwise. Note that the clockwise convention can be reversed if needed in DirectX.

Backface culling refers to the process of discarding back-facing triangles from the pipeline. This can potentially save a lot of processing time.

// Vertex Attribute Interpolation

We can attach attributes to triangles’ vertices such as colors, normal vectors, and texture coordinates. These attributes need to be interpolated for each pixel covering the triangle. In addition, vertex depth values need to be interpolated so that each pixel has a depth value for the depth buffering algorithm.

The vertex attributes are interpolated in screen space so that the attributes are interpolated linearly across the triangle in 3D space (so called perspective correct interpolation). This allows us to use vertex values to compute the values for interior pixels. Again, the hardware handles this for us, so you do not need to worry about the math behind it.

The Pixel Shader Stage

Pixel shaders are program we write that are executed on GPU. A pixel shader can do lots of things, ranging from per-pixel lighting, reflections, and shadowing effects.

The Output Merger Stage

After pixel fragments (the pixels covered by one triangle) have been generated by the pixel shader, they move onto the output merger (OM) stage of the rendering pipeline. Some pixel fragments are rejected (like from the depth or stencil buffer tests), and the rest are written to the back buffer. Blending is also done in this stage, where pixels may be blended with the pixel currently on the back buffer - some effects like transparency are done with blending.

This overview of the stages gives us a high-level understanding of the order of each step, as well as what each step accomplishes. In chapter 6 of 3D Game Programming With DirectX 12, the actual DirectX API interfaces and methods will be focused on, showing how all of this is actually accomplished in code.

Here’s an excellent YouTube video that provides a lot of helpful visualizations for the aforementioned topics: How Do Video Game Graphics Work?